Introduction: Alzheimer’s disease is a multifaceted neurodegenerative condition predominantly associated with aging and is marked by a gradual decline in cognitive function, memory loss, and behavioral changes. This condition affects millions globally, creating considerable challenges not only for patients but also for their families and caregivers. As the leading cause of dementia, Alzheimer’s progressively impairs brain function, often starting subtly but eventually interfering with the individual’s ability to perform daily tasks. A critical consideration in Alzheimer’s disease research is whether it should be classified as a disability. Such classification could have significant implications for patients’ access to support systems, healthcare services, and legal rights. Recognizing Alzheimer’s as a disability could facilitate better access to essential resources and protections, which is particularly important given the challenges associated with maintaining independence and quality of life. Furthermore, this designation could influence healthcare policies, public perceptions, and insurance coverage, impacting patients and families both financially and emotionally.

The objectives of this analysis are twofold: first, to investigate Alzheimer’s as a potential disability, reviewing perspectives from legal, medical, and social viewpoints; and second, to present ten notable facts about Alzheimer’s to enhance understanding of the disease. Through this examination, this essay seeks to elucidate the complexities of Alzheimer’s, provide insight into the disability classification debate, and promote a deeper awareness of its societal and individual impacts.

Table of Contents

What is Alzheimer’s?

Alzheimer’s disease is the leading cause of dementia, a broad category of disorders that impair memory and other cognitive functions to a degree that disrupts daily living. Alzheimer’s disease is responsible for 60-80% of all dementia cases. Unlike normal aging, which may involve mild brain shrinkage without significant neuron loss, Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by widespread brain damage. In this condition, numerous neurons cease to function effectively, lose their connections with other neurons, and ultimately degenerate and die.

Early symptoms of Alzheimer’s include:

- Forgetting recent conversations or events

- Misplacing objects

- Forgetting the names of places and common objects

- Difficulty finding the right words

- Asking repetitive questions

- Demonstrating poor judgment or decision-making difficulties

- Becoming less adaptable and more reluctant to engage in new activities

The disease likely results from a combination of age-related changes in the brain, genetic predisposition, environmental exposures, and lifestyle factors. The impact of these risk factors may vary between individuals. The primary risk factor for Alzheimer’s is increasing age, with most cases occurring in individuals aged 65 and older. When Alzheimer’s disease affects individuals under the age of 65, it is classified as younger-onset or early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. People with younger-onset Alzheimer’s can experience the early, middle, or late stages of the disease.

The Division of Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology offers thorough diagnostic assessments and evaluations for individuals with neurological disorders. Specialists in behavioral neurology are trained to assess and manage patients with brain conditions that impact cognitive functions, such as memory and thinking, including Alzheimer’s disease. These professionals provide diagnostic services, consultations, and counseling to patients, as well as support for families and caregivers. Currently, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. However, treatments are available that may influence the progression of the disease, and both drug and non-drug interventions may help manage symptoms. Understanding these treatment options can support individuals with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers in coping with symptoms and enhancing quality of life.

Is Alzheimer’s disease considered a disability?

Disability is best understood as a spectrum rather than a distinct classification. The term “disability” can hold varied definitions depending on the context. Medically, it denotes a condition where symptoms hinder an individual’s capacity to perform standard activities.

Is Alzheimer’s disease considered a disability? Alzheimer’s disease is considered a disability in this framework, as individuals with this condition invariably develop significant impairments over time. However, definitions of disability can differ in various contexts. For instance, someone with mild Alzheimer’s symptoms may identify as having a disability as their symptoms affect daily life, yet they may not meet eligibility criteria for disability benefits until symptoms become more severe. Notably, Early Onset Alzheimer’s disease is recognized as a qualifying condition for disability in the Social Security Administration’s Blue Book. In such cases, a diagnosis alone meets the criteria for Social Security disability, and claims related to this diagnosis are often processed swiftly.

Before reading the questions and answers below, it is better to listen to: Early Signs of Alzheimer’s Disease and a Comprehensive Approach to Addressing Memory Loss with Dr. Heather Sandison.

10 interesting answers about questions asked for Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder marked by cognitive, behavioral, and social function impairments. This condition raises numerous common questions about dementia, reflecting a need for comprehensive understanding.

Is freezing a symptom of Alzheimer’s?

Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease often exhibit symptoms beyond cognitive impairment, including agitation, sleep disturbances, and hallucinations. Behavioral symptoms such as wandering, pacing, and atypical actions are also common, posing additional challenges for caregivers. Hypothermia risk is elevated in dementia patients, as their ability to regulate body temperature can be compromised. This condition, characterized by accelerated heat loss, leads to confusion, disorientation, and shivering, exacerbating cognitive difficulties.

Does gabapentin cause dementia or Alzheimer’s?

Gabapentin use is associated with potential side effects, including peripheral edema, weight gain, and visual disturbances. Gastrointestinal effects such as diarrhea have also been reported. Patients prescribed gabapentin should refrain from operating vehicles until its effects on their alertness and motor skills are understood. More rarely, severe adverse reactions include suicidal ideation, behavioral changes, particularly in pediatric patients, and mood disturbances. Long-term gabapentin therapy necessitates monitoring for potential impacts on the patient’s emotional and psychological well-being. Reports indicate that some patients may experience mood changes, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts. Additionally, gabapentin treatment has been linked to cognitive impairments, such as decreased memory, executive function, and attention, especially in patients with spinal cord injury.

Why do Alzheimer’s patients sleep so much?

Excessive daytime and nighttime sleep are a prevalent symptom among individuals with dementia, particularly in its later stages. This sleep pattern often raises concerns among family members and caregivers, who may fear it signals a progression of the disease.

Is it normal for Alzheimer’s patients to sleep a lot? Research findings indicate that the neural networks governing wakefulness are notably impaired in Alzheimer’s disease. Earlier studies proposed this association, and recent investigations have confirmed that the neurons responsible for maintaining alertness are indeed damaged in Alzheimer’s patients who exhibit excessive daytime sleepiness.

Watch Now: What’s the connection between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease?

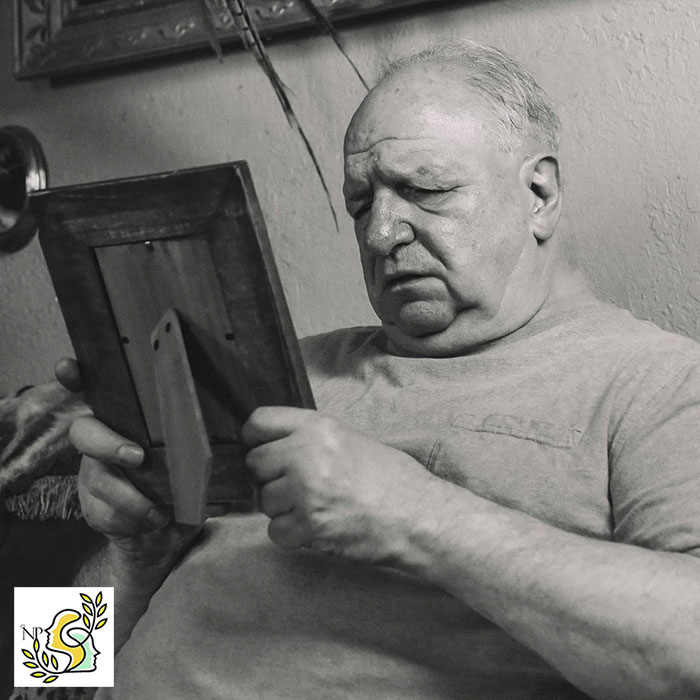

Do patients with Alzheimer’s feel pain?

As dementia advances, the likelihood of pain increases, with approximately 50% to 80% of individuals with moderate to severe dementia experiencing daily pain. Despite this prevalence, many patients receive insufficient pain management, often due to challenges in recognizing pain. Alzheimer’s disease, in particular, can result in a mask-like facial expression that obscures typical indicators of discomfort, such as a grimaced mouth or furrowed brows. Additionally, patients may lack the cognitive ability to verbally express their pain, limiting their ability to communicate discomfort with phrases like “these hurts” or “I am in pain.” Managing this pain effectively, in collaboration with the patient’s care team, can significantly enhance their comfort, reduce distress, and minimize symptoms such as aggression, social withdrawal, and episodes of delirium.

Should you tell someone with Alzheimer’s that they have it?

Individuals diagnosed with dementia exhibit diverse responses to their diagnosis, often finding it challenging to process or adapt to the implications. For some, there may be an absence of awareness regarding their cognitive changes, leading to the perception that nothing is amiss. Research generally suggests that, if a patient inquires directly about their condition, an honest response can be beneficial. Understanding that their symptoms result from a medical condition, rather than a perceived loss of sanity, may provide a sense of relief. While disclosing the diagnosis to those who do not explicitly ask can be helpful—especially if the individual seems concerned—caregivers should respect a patient’s expressed wish not to know. Communicating the diagnosis might evoke an emotional response in the individual with dementia and, in certain cases, could exacerbate distress.

Does Alzheimer’s cause headaches?

The extent of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease patients is directly associated with the intensity of pain they may experience. This suggests that patients without an identifiable source of pain may still be enduring significant discomfort, potentially due to neuroinflammation in the brain. A large, population-based study analyzing patient survey data revealed that individuals with dementia reported a higher prevalence of headaches, including both migraine and non-migraine types, compared to individuals without dementia.

Which senses is most affected by Alzheimer’s disease?

Alzheimer’s Disease is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive memory impairment, cognitive deficits, and disruptions to daily functioning. Individuals with dementia often exhibit altered emotional responses, with diminished regulation over emotions and expression. These changes may manifest as heightened reactions, sudden mood shifts, or irritability. Conversely, affected individuals may also appear unusually detached or disengaged from their surroundings.

A prominent challenge associated with AD is the impairment of visual capabilities. Research has demonstrated that visual dysfunction is a particularly distressing symptom for individuals with Alzheimer’s, as it affects their ability to navigate environments, recognize faces, and engage in daily tasks. One study highlighted the occurrence of visual agnosia in AD patients, where individuals, despite having normal vision, are unable to recognize familiar faces. This condition exacerbates dependency on caregivers, contributing to increased frustration. As the disease progresses, visual impairment, along with deficits in visual perception and contrast sensitivity, tends to worsen.

Why are Alzheimer’s patients afraid of water?

In the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, individuals often exhibit heightened anxiety and agitation as they become aware of their cognitive decline and the severity of the condition. Over time, this anxiety may be driven by concerns about being left alone or abandoned, and disruptions to their daily routine can further exacerbate feelings of distress. Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease may also experience various fears associated with water, including:

- Fear of falling: Impaired judgment of water depth and temperature, or concerns about losing balance, may contribute to this fear.

- Fear of drowning: There is often heightened anxiety surrounding water, particularly when water is poured over the head.

- Fear of vulnerability: Feelings of vulnerability and embarrassment may arise from being undressed during bathing.

- Fear of loss of control: Individuals may experience a sense of helplessness or powerlessness during activities like bathing.

- Confusion regarding temperature: Cognitive impairments can lead to difficulty distinguishing between hot and cold sensations.

- Discomfort during bathing: Bathing may be perceived as unpleasant due to physical discomfort or emotional distress.

- Loss of privacy: Assistance during bathing may result in feelings of discomfort or a loss of privacy.

- Communication difficulties: Challenges with communication may occur, especially when individuals are required to remove glasses or hearing aids.

Additionally, bathing can be distressing for individuals with Alzheimer’s, due to the uncomfortable environment (e.g., cold bathrooms), sensory overload (e.g., water hitting the skin), feelings of vulnerability (e.g., being disrobed), the overwhelming sound of running water, and fear of falling.

Is Alzheimer’s considered a mental illness?

Although Alzheimer’s disease shares some characteristics with mental illnesses, it is not considered a mental health disorder. Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that leads to the progressive deterioration of cognitive functions, including memory and thinking abilities. It is a specific form of dementia, a category of disorders that impairs memory, cognition, and behavior.

As the disease advances, symptoms become increasingly severe, disrupting the individual’s ability to perform daily activities. Dementia is distinguished from mental illnesses, such as depression, by its gradual onset and continuous progression, with the rate of decline varying depending on the specific type of dementia.

What neurotransmitter affects Alzheimer’s?

The onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is likely influenced by a complex interplay of age-related brain changes, along with genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. The contribution of each of these factors to the risk of developing Alzheimer’s may vary across individuals.

In Alzheimer’s patients, there is a reduction in both the concentration and functionality of acetylcholine (ACh), a neurotransmitter critical for memory processing and learning. Additionally, glutamate and its receptors play a key role in long-term memory formation and long-term potentiation, a mechanism thought to underpin learning and memory. Alterations in serotonin (5-HT) levels have also been associated with the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

Conclusion

In summary, Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the progressive deterioration of cognitive functions, including memory and the ability to perform everyday tasks, ultimately resulting in disability. As a form of dementia, Alzheimer’s impairs the brain’s capacity to process critical functions such as thought, problem-solving, and memory retrieval. This progressive decline leads to a loss of independence in affected individuals, often necessitating escalating levels of care and support from caregivers. The ten facts outlined underscore the complexity and increasing prevalence of Alzheimer’s, as well as its significant effects on individuals and society. The disease not only imposes physical and cognitive impairments but also introduces substantial social, emotional, and economic challenges for families and healthcare systems. Despite ongoing research efforts, there is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s, highlighting the urgent need for continued medical advancements, public awareness, and support for those living with the condition. Recognizing Alzheimer’s as a disability is critical for promoting inclusive policies, improving care strategies, and enhancing the overall quality of life for affected individuals.

Frequently Asked Questions

Frequently Asked Questions about Alzheimer’s:

Does stress cause Alzheimer’s?

Current research indicates that stress may play a role in the development or progression of dementia, but does not necessarily cause dementia

Is Alzheimer’s a disability for social security?

Yes, people with Alzheimer’s in the United States qualify for SS disability benefits under Blue Book’s Section 11.00 Neurological Adult and Section 12.00 Mental Disorders.

Is Alzheimer’s classed as a disability?

Alzheimer’s disease is a disability because, eventually, all people with the condition develop severe symptoms.

Some people say why do people with Alzheimer’s sleep so much?

For some people, it may be that their internal ‘biological clock’, which judges what time it is, becomes damaged so the person starts to feel sleepy at the wrong time of day.

Can Alzheimer’s cause headaches?

Those with dementia were more likely to report any type of headache (including migraines and non-migraine headaches) compared with those without dementia.

Is Alzheimer’s a mental disability?

Alzheimer’s is a disability because it significantly affects a person’s ability to carry out their usual tasks and, ultimately, to live independently.

Is Alzheimer’s a developmental disability?

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder of higher age that specifically occurs in human.

Reference:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38381674

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38402606

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38159571

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37866486

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37956598

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37963840

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38254235

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38172602

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37698424

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38640162

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33667416

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32484110

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28872215

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30135715

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36613544

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31753135

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33609479

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33950641